A trip by sailboat is one of the slowest ways of getting

from A to B.

So why, so often, does it not feel that way?

There were two surprises I will always remember from my first ever sailing experience. One was seeing the distance we’d covered on a map at the end of that day, the other was seeing the plaster cast that covered my left leg at the end of that day.

There were two surprises I will always remember from my first ever sailing experience. One was seeing the distance we’d covered on a map at the end of that day, the other was seeing the plaster cast that covered my left leg at the end of that day.

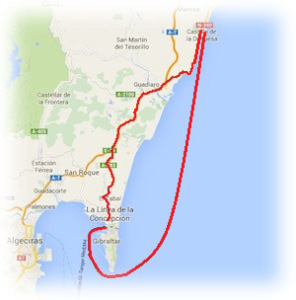

I was recently reacquainted with one of these surprises and, unusually for me, it wasn’t the painful, inconvenient one. I recently had the opportunity to day sail the twenty or so miles along Spain’s Costa del Sol coastline from Duquesa to Gibraltar and then repeat the same trip just over a week later by bus.

It was an opportunity to remind myself again just how much one’s perception of time and distance can get distorted at sea.

And ponder just why that is.

By sea

We were up and about bright and early for that first day’s sail, probably because we’d all flown in the previous day and fatigue had kept the previous night’s drinking to a minimum.

We were up and about bright and early for that first day’s sail, probably because we’d all flown in the previous day and fatigue had kept the previous night’s drinking to a minimum.

Clear blue skies greeted us and the mirror-flat sea mocked us; wind was notably absent both in the present and in the forecast. We weren’t too concerned though as our first day out wouldn’t be a long trip anyway. We’d decided on a gentle, boat-familiarising hop along to coast to Gibraltar. Only the skipper had been there before and we were as keen to visit it as he was to pick up some duty free booze “for the boat”.

An easy pilotage out of Duquesa found us quickly motoring sou-sou-west towards Europa Point and the unmistakable hump of Gib. Viewed from Spain the Rock of Gibraltar puts one in mind of a giant British middle finger raised squarely in the face of the surrounding land. One can sympathise, at least a little with Spain’s irritation at Britain possession of it, at least until you remember Spain’s similarly unequivocal possession of Ceuta on the African side of the Strait.

An easy pilotage out of Duquesa found us quickly motoring sou-sou-west towards Europa Point and the unmistakable hump of Gib. Viewed from Spain the Rock of Gibraltar puts one in mind of a giant British middle finger raised squarely in the face of the surrounding land. One can sympathise, at least a little with Spain’s irritation at Britain possession of it, at least until you remember Spain’s similarly unequivocal possession of Ceuta on the African side of the Strait.

The flat calm was a useful opportunity for the newbies aboard to play with the helm and get acquainted with the galley kettle as we watched the Costa slip by and Gib grow larger. A useful wind started to build over our port quarter as we approached the Strait and we were able to give the engine a rest and sail the rest of the way. As Europa Point came alongside in the Strait itself we grabbed a sandwich and prepared ourselves for the pilotage in.

We arrived at siesta time so had a little wait at the visitor’s quay before sorting the paperwork and getting a berth allocated. We were tied up and enjoying our first beer of the day in a sun-baked cockpit a little after three in the afternoon.

A bit of motoring, a bit of sailing, a bit of sun and the fleshpots of Gibraltar awaiting us that evening after a shower and change of clothes. What more could you ask for?

By land

The Costal del Sol was more Costa del Smog when I woke up for my last full day before flying home. With the grot forecast to give way to a windless sunny day later and with only myself and the skipper left on the boat, taking her out didn’t enthuse either of us. We decided therefore to hop on the bus to Gibraltar for some end-of-trip duty frees.

The Costal del Sol was more Costa del Smog when I woke up for my last full day before flying home. With the grot forecast to give way to a windless sunny day later and with only myself and the skipper left on the boat, taking her out didn’t enthuse either of us. We decided therefore to hop on the bus to Gibraltar for some end-of-trip duty frees.

Captain Ben, as I think I’ve mentioned elsewhere, is a scrawny wee runt yet even I was nervous sitting on the bench of the rickety bus shelter on the main road outside Puerto de la Duquesa lest I bring it toppling down on top of me (fatties beware!) The busses run every hour or so and ours was only a trifle late. I managed to stay my instinct to look left rather than right for oncoming traffic just enough for us to see it coming and catch it.

Over the next hour the straight highways gave way to twisting, turning roads through the undulating Andalucía countryside. The day before Easter and a big public holiday in Spain we stopped frequently to take on passengers with the same agenda as ourselves; only for them it was pre-holiday duty frees rather than post-holiday ones they were drawn by.

I stared out of the window as the towns and countryside sped by, I listlessly toyed with the paperback in my backpack, I exchanged the odd few words with the skipper – though after a fortnight we’d reached the comfortable and quintessentially blokeish stage when words were sparing (at least when we were sober).

I stared out of the window as the towns and countryside sped by, I listlessly toyed with the paperback in my backpack, I exchanged the odd few words with the skipper – though after a fortnight we’d reached the comfortable and quintessentially blokeish stage when words were sparing (at least when we were sober).

We finally arrived at La Linea bus station, a short walk from the Gibraltar land border we’d crossed just a week before and a mere stones throw away from the marina we’d berthed in that day. It had been around an hour. It seemed longer. It had been just over twenty miles. It seemed further.

I was bored and ready for a walk.

I was hungry and ready for lunch.

I was going home soon and ready for some duty free scotch.

By coincidence

To be entirely fair, public transport is an imperfect comparison class to sailing; driving would be a better one. An hour for a twenty mile journey by road is hardly stellar and following a bus route with regular stops doesn’t help. Five hours for twenty miles in a small sailboat with regular changes of course and close-quarters pilotage at either end is, on the other hand, respectable if not impressive.

Nonetheless I’m struck by how much shorter the distance felt by sea and how much quicker the time passed. By comparison the road trip seemed endless, a much longer distance over a disproportionately long time. There is just as much world to see when travelling by land and much more humanity to watch too, so why did it seem longer, further and duller?

Preconceptions may play a part here. We perceive road travel as quick, air travel as very quick, sea travel as slow. A journey by boat is perhaps more likely to surprise us on the upside and road travel surprise us on the downside.

Personally though, I think “activity” is the answer I’m looking for here. Sailing is a rotten means of getting from A to B – most of us could jog faster than the average sailboat – so when travel is about the end, rather than the means, few would choose to do it this way. For me, and I suspect the majority of sailors, travel is neither the end nor the means when we sail. We sail for the sailing, sailing is our activity and the travel is merely a pleasant side effect.

We sail for the sailing and perhaps therefore the distance we travel when we do will always have the ability to surprise us. Since it isn’t why we’re out there we can be forgiven for being surprised we’ve travelled any distance at all.

While I freely and unashamedly admit my culpability for the majority of boat-borne balls-ups I’ve been party to in my time, those of the culinary variety are seldom down to me.

While I freely and unashamedly admit my culpability for the majority of boat-borne balls-ups I’ve been party to in my time, those of the culinary variety are seldom down to me. 1. Suffering a little wind?

1. Suffering a little wind? 2. Table d’hôte? Just say no.

2. Table d’hôte? Just say no. 3. It’s okay, we’ve got some on board

3. It’s okay, we’ve got some on board 4. It’s a gas, man

4. It’s a gas, man 5. What no chip pan?

5. What no chip pan? 6. Smokin’

6. Smokin’ 7. Water, water, everywhere, nor any drop to drink

7. Water, water, everywhere, nor any drop to drink 8. Power cut

8. Power cut 9. Seaman Stains

9. Seaman Stains Boating newbies who’ve done any sort of research usually join a boat in absolute terror of the toilet. Marine loos have an unduly bad reputation driven more by the prospect of disassembling the sewage pipes to clear a blockage than the chances of a blockage itself.

Boating newbies who’ve done any sort of research usually join a boat in absolute terror of the toilet. Marine loos have an unduly bad reputation driven more by the prospect of disassembling the sewage pipes to clear a blockage than the chances of a blockage itself.

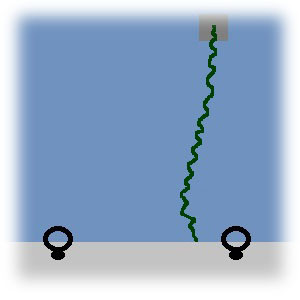

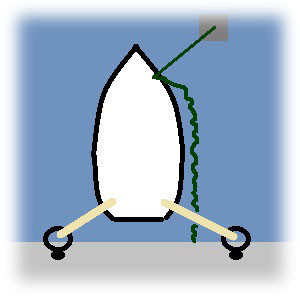

For the uninitiated a lazy-line is a rope dangling from the floating pontoon or harbour wall which leads back to a seabed mooring some distance off the quay. The idea is that you reverse the boat against the quay and make her stern fast against it, then pick up the lazy-line, walk it forward hand-over-hand, take up the slack against the mooring and make the bow fast to that too. The boat is then held securely by two shorelines at the stern and one mooring line at the bow.

For the uninitiated a lazy-line is a rope dangling from the floating pontoon or harbour wall which leads back to a seabed mooring some distance off the quay. The idea is that you reverse the boat against the quay and make her stern fast against it, then pick up the lazy-line, walk it forward hand-over-hand, take up the slack against the mooring and make the bow fast to that too. The boat is then held securely by two shorelines at the stern and one mooring line at the bow. It’s a fairly straightforward system which allows the sailor easy stern-to access to the shore whilst allowing the marina owners to pack the boats in – quite literally – like sardines. And in benign conditions with little wind across the bow and no tide to worry about it’s a pretty easy one to master, even more so when the marineros – ubiquitous in many Med marinas – oblige by both securing your stern lines and handing over the lazy-line for you.

It’s a fairly straightforward system which allows the sailor easy stern-to access to the shore whilst allowing the marina owners to pack the boats in – quite literally – like sardines. And in benign conditions with little wind across the bow and no tide to worry about it’s a pretty easy one to master, even more so when the marineros – ubiquitous in many Med marinas – oblige by both securing your stern lines and handing over the lazy-line for you. Never let the slime-line slip through your hands; keep a firm hold with one hand and keep the other clear while advancing. A pair of light deckhand’s gloves can be really useful though they will need a good wash afterwards.

Never let the slime-line slip through your hands; keep a firm hold with one hand and keep the other clear while advancing. A pair of light deckhand’s gloves can be really useful though they will need a good wash afterwards.