Facing your first turn in the galley any time soon?

Perhaps a few episodes of Captain Ben’s Kitchen Nightmares could help.

While I freely and unashamedly admit my culpability for the majority of boat-borne balls-ups I’ve been party to in my time, those of the culinary variety are seldom down to me.

While I freely and unashamedly admit my culpability for the majority of boat-borne balls-ups I’ve been party to in my time, those of the culinary variety are seldom down to me.

This isn’t the result of any talent, ability or indeed basic competence on my part. It’s largely down to a studied and accomplished avoidance of sailing with skippers who do much other than day-length hops and who usually have the evening’s bar(s) and restaurant planned out before the day’s passage is charted up.

I’ve also found that bagging washing the dishes as quickly as possible helps dodge having to prepare the dishes first.

If you’re planning any serious crewing though, the chances are you’re going to end up doing at least a turn or two in the galley before too long. Whether you’re a complete culinary clod (like myself) or whether you make Gordon Ramsey look like a Burger King patty-flipper, transferring your skills to the poky confines and scarce resources of a sailboat’s galley won’t necessarily be, er, plain sailing.

Here then are Captain Ben’s ten random tips for the first time galley-hand.

1. Suffering a little wind?

1. Suffering a little wind?

Not, in this case, of a gastric variety (though that can quickly make you unpopular amongst the other crew in the confines of a thirty-odd footer overnight) but wind of the atmospheric variety. Sailboats and a breeze kinda go hand-in-hand and even when you’re motoring in a dead calm you’ll still be making a fair few knots of apparent wind yourself.

If you’re planning meals to be served on deck and on passage it’s as well to bear this in mind as a plate of salad will likely only be appreciated by the lucky fish it lands near when it blows overboard. Such dishes are best left for down below, in port or in a quiet anchorage.

The movement of a boat can make full cups of hot drinks something of a health risk and a positive weapon of mass destruction when changing tack. Best to keep them little over half full and stand them in the sink when filling them from the kettle.

2. Table d’hôte? Just say no.

2. Table d’hôte? Just say no.

If you’re a bit of a hand in the kitchen and thinking of impressing your boat-mates with a bacchanalian banquet, a choice of mains and an amusing selection of wines and digestifs, pause for a moment and imagine doing it all in constantly moving walk-in-closet with just a camping stove for company.

You’re likely to come a cropper!

Okay, it’s not quite that bad but you’re not going to have the facilities you’re used to at home. A typical sailboat “galley” has enough room for one person or two frotteurists to work comfortably. You’ll have a small sink, limited worktop space, a small oven and two small hobs to work with. And if you’re preparing a meal on passage the whole lot will be constantly pitching and rolling. Marine ovens are gimballed so they stay reasonably flat at sea, though only in one direction.

I have sailed with a skipper who rightfully takes pride in his ability to prepare an impressive three-course meal on his boat, but that takes a lot of planning, practice and experience to pull off. For the rest of us, the KISS principle wins here – keep it simple, stupid!

3. It’s okay, we’ve got some on board

3. It’s okay, we’ve got some on board

Skippers are, on the whole, a bunch of tight-wads matched only by the tightness of the stowage space on their boats. For both these reasons they’ll be quick to tell you “Oh, we’ve got some of that on board” when you’re out getting supplies and you mention any ingredient you mightn’t actually need to buy.

Don’t believe a word of it!

It’s not that they’re lying, it’s just that sea air and sea water will corrode cans and turned dry goods into growth covered blocks of granite at a rate of knots their boat would only reach if you pushed it off of a cliff. If it’s important to what you’re planning to make, check the state of it on board before you head to the shops.

4. It’s a gas, man

4. It’s a gas, man

Marine ovens aren’t just small, they can be a little temperamental too.

Some can burn as well as a home oven but in my experience most struggle to come close so any dishes that require high cooking temperatures may well leave the crew hungry for long enough to cause a mutiny (even more likely if you run out of gas before you’re finished).

They all have safety devices that cut the gas supply off if it isn’t burning, which usually means you have to hold the knob in for a few seconds after the oven or hob has lit or it’ll cut out. They usually also have an ignition system which runs off the domestic battery supply but I can honestly say I have NEVER sailed on a boat where this works. Therefore you’ll have to juggle turning the knob, holding it in and lighting the gas with a match or lighter at the same time. This is especially entertaining in heavy weather and getting it wrong more than a couple of times usually means you’ll set off the gas alarm too.

5. What no chip pan?

5. What no chip pan?

A skipper of my acquaintance tells of how her jaw nearly hit the floor when one of her crew positively insisted on cooking chips (French-fries) for dinner, a crew member who was equally shocked (though indomitably undeterred) when told there was no chip pan aboard.

Deep-frying also has a tendency to give off rather a lot of hot, smoky vapour, which leads me nicely on to…

6. Smokin’

6. Smokin’

Due to the general flammability of the average boat, not to mention the tank of fuel, gas cylinders and other incendiary essentials on board, you’ll tend to find at least one or two nice, loud smoke alarms and heat detectors knocking about down below. Setting one off during a delicate berthing manoeuvre has been responsible for at least one dented bow I’ve witnessed and is sure to have the skipper heading ashore to buy a plank for you to walk.

Close cabin doors that have fire and heat detectors behind them when preparing anything that might set them off, open any vents or windows in the main cabin if you’re somewhere sheltered (not in a force nine at sea or you’ll sink!) and leave your electric smoker at home – it probably won’t run on 12 volts anyway.

7. Water, water, everywhere, nor any drop to drink

7. Water, water, everywhere, nor any drop to drink

The dull sound, like a pneumatic drill in slow motion, made by the pressurised water pump is a noise anyone who’s sailed a reasonably modern or well-equipped boat will instantly recognise. It’s more than just an annoyance to slumbering crew, it’s also an alert to the skipper that someone is depleting “his” water supply.

The extent to which fresh water preservation is an issue will depend on the type of sailing you’re doing. If you’re day hopping from marina-to-marina, replenishing the tank is just a regular chore. If you’re crossing an ocean though water will be strictly rationed. Your lives kinda depend on it after all.

In either case though, wasting water isn’t going to make a good impression. Getting used to drawing only what you need is good practice at the very least and staves off a little further the next time someone has to sit on deck for quarter of an hour pointing a hose into the water filler cap when they’d rather be in the pub.

8. Power cut

8. Power cut

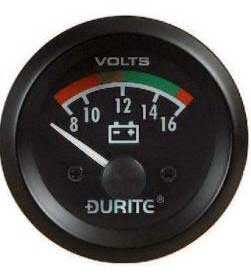

Environmentalists would love the domestic side of sailing; it’s all about preservation of resources after all. Continuing this theme it’s not just gas and water supplies you need to be mindful of, but also electricity.

Anything electrical on a boat, when it isn’t hooked up to shore power, usually runs off two or three car batteries and the power in them is rather important for little things like starting the engine, powering your navigation lights and feeding the GPS. Leave the fridge open when you’re not actively using it and you can be sure the skipper will be pointing all of this out to you (at considerably greater length than I just did).

9. Seaman Stains

9. Seaman Stains

Another of my regular skips keeps his boat rather like a sit-com character would keep a garden shed. It is, in a nutshell, the most chaotically disorganised, tumbeldown mess I’ve ever set sail in. He’s indubitably the least anal-retentive skipper I know.

With two exceptions.

His upholstery and his teak.

10. Down the plughole

Boating newbies who’ve done any sort of research usually join a boat in absolute terror of the toilet. Marine loos have an unduly bad reputation driven more by the prospect of disassembling the sewage pipes to clear a blockage than the chances of a blockage itself.

Boating newbies who’ve done any sort of research usually join a boat in absolute terror of the toilet. Marine loos have an unduly bad reputation driven more by the prospect of disassembling the sewage pipes to clear a blockage than the chances of a blockage itself.

The toilet isn’t the only tight orifice waste has to negotiate aboard a boat. The sort of food scraps you’d think nothing of rinsing down a domestic sink can easily render the one in the galley hors de combat. Coffee grinds and rice are particularly adept at doing this.

Clearing a sink blockage is a lot less onerous than clearing one in the heads but can still entail an awful lot of kit being pulled out of lockers and panels being removed. Your skipper mightn’t thank you for making sure as much waste food as possible goes in the bin or over the side, but he’ll be monumentally pissed if you don’t.

Or you could just do as Captain Ben does. Pick your skippers, be the first to volunteer for the dishcloth and so long as you can whip up a quick Ginsters and cup-a-soup when you pick a wrong ‘un, you’ll do just fine.