Close-hauled is one of the easiest points of sail to helm.

So why are so many rookies uncomfortable with it?

In his oft-quoted (and, at least in name, oft parodied) 1974 classic Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance Robert Pirsig revisits his early years as a Montana State professor restlessly striving to educate more effectively

“Schools teach you to imitate. If you don’t imitate what the teacher wants you get a bad grade. “

At one point on his journey he comes to a realisation that grading students on an ongoing basis was subverting the learning process; driving students to both pursue and to be comforted by their grades rather than genuinely focussing on thinking and learning.

“Originality on the other hand could get you anything – from A to F. The whole grading system cautioned against it.”

And so he embarked on a successful, if somewhat unpopular experiment of withholding his students’ grades until the end of the course and thus removing all the feedback along the way that, in his view, obstructed the learning process.

“Eliminate the whole degree-and-grading system and then you’ll get real education.”

Close-hauled is one of the easiest (if sadly coldest) points of sail a helmsman encounters, yet sailing greenhorns often seem to struggle to get comfortable with it. Out sailing recently with a somewhat annoyingly fast-learning rookie and watching him struggle a little with the rhythm of close-hauled helming, I got to wondering whether the problem with learning this point of sail lies in our approach to, and reactions to, learning itself.

The art of close-hauled helming

If you don’t know what close-hauled means I’m rather surprised you’ve bothered to read this far and frankly I have to caution you that this post isn’t going to get any more interesting for you.

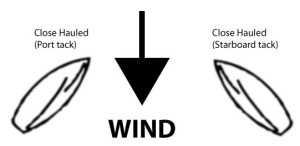

For anyone sticking around though, so called points of sail refer to the rough direction the wind is coming from relative to the direction the boat is pointing. Mainstream sailboats (the ones with two triangular sails down the centreline) can sail to within around forty-five degrees of where the wind is coming from. So if, for example, the wind is from the north then the boat can sail northeast, northwest and any direction south of those but not directions north of them. Depending on the quality of the boat and the rig they may well be able to get much closer to the wind, say to thirty degrees off it rather than forty-five.

When sailing as “close” as possible to the wind (or close to as close as possible) this point of sail is described as close-hauled. The sails will be winched (or indeed “hauled”) in as tightly as possible and act rather like wings to pull the boat in a direction towards the wind.

And it’s a comparatively easy one to steer because often the compass course is irrelevant as our destination lies to windward of where we’re pointing so we just want to be as close to the wind as we can get whilst making good speed. If you steer too close to the wind the boat will tell you by slowing down and levelling up with the sails starting to flap. If you steer too far off the wind she’ll speed up and heel over more. It’s pretty obvious which way you need to turn the wheel or swing the tiller when either of these happens.

Harden up

To quote Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance again, “For every fact there is an infinity of hypotheses.” I suspect Pirsig would have got on well with boat skippers who as a group (if not as individuals) certainly seem to believe that for every task there is an infinity of ways to do it.

With modern cockpit instruments displaying the exact wind direction prominently in the helmsman’s face it’s possible to take the best angle for the boat and try to keep her on it. If the boat sails well at thirty-degrees, keep the arrow on the 30, harden up when it strays over and bear away when it goes under.

This is workable but not terribly efficient. Every movement of a boat’s rudder acts as a brake that slows your progress and if your destination is to windward of where you’re pointing, every bit of progress you can make upwind is to the advantage. So while you still need to correct the boat closer to the wind when she strays too far off there is merit in letting her round up until you feel she’s starting to lose power and then bear away back to a better wind angle.

This is good advice oft heard yet oft not well followed. And I think herein lies a problem with our attitude to education.

Bear away

That sailing instructor who tells you to let the boat round up into the wind while she still has power as opposed to steering her off it promptly will be the same sailing instructor who ten minutes later will spot that you’re sailing too close to the wind and tell you to bear away. It feels like a reprimand, it feels like you’re doing something wrong. It’s like a bad grade.

And none of us like bad grades.

So it seems to me that rookie helms don’t follow the first advice because of an innate desire to avoid the second rebuke.

Perhaps effective teachers may be well advised to withhold their grades from time-to-time and let the helmsman learn for themselves. And perhaps effective students may be well advised to blinker themselves a little to the grades they’re getting from time-to-time too.